The Shnookals at Shoreham by Liezl Shnookal

A family history at Shoreham that began in 1952 and continues to this day — told with love for family, and love for Shoreham.

Ruth and Laurie Shnookal fell in love with Shoreham the very first time they visited, and it’s a love story that was to last their whole lives.

On 28th February 1952, they stood together and gazed at the block of land they had just purchased. They could hardly believe that it was theirs, their own little piece of Shoreham. They had paid €160 for almost an acre of land, a paddock within the brand-new subdivision along Marine Parade. Hand in hand, Ruth and Laurie looked out over the glorious sea view. Suddenly, a cry from their young daughter signalled that she had woken up, and the child was quickly taken out of the car to be shown the block. Afterwards, Laurie Shnookal drove his little family back home to St Kilda, talking excitedly about his plans for a ‘bush shack’ on their ‘country property’. Ruth, who was brought up in outback South Australia, smiled at this but was just as thrilled.

Two years later, the Shnookals had a holiday house at Shoreham. One Sunday afternoon in early 1954, Laurie stopped the car on the main road to admire his ‘shack’ and took this photo.

It had been a huge achievement to build the place. For while Laurie’s enthusiasm knew no bounds, his spare time was in short supply. Fortunately, he had many friends, and so with their help, plus some from a paid carpenter, a house was finally constructed. The house stood alone in an empty paddock, its fibro-cement sheeting walls up, all of its windows installed, and the corrugated iron roof securely fastened. Even the rainwater tank was on its stand and catching run-off from the roof, although not yet plumbed into the house. Laurie was exhausted but content.

I arrived at the end of 1954, Ruth and Laurie’s third daughter, just in time for the Shnookal’s first Christmas holidays in the completed house. There was still no electricity; however, my mother proved to be an expert at filling up the lamps with kerosene and keeping the wicks trimmed for the maximum amount of light. Ruth’s childhood in a remote farmhouse without power proved to be an excellent preparation for those early days at Shoreham. It was she who oversaw the building of a very serviceable outside toilet, complete with a dunny can and a wooden seat. This was a very welcome addition for everyone, including visitors. Here are some of our special visitors: - Ruth’s mother, Nancy, her sister Eleanor and Tony Valentine. Also pictured is Ruth herself, plus Shan, Deb and me (the baby).

I wasn’t the youngest Shnookal for long, for my sisters and I were joined by our brother, Toby. By 1957, we had neighbours on Marine Parade, and the area was beginning to look quite different. Power poles had gone up, and our house was by then connected to the grid. An open fireplace had been built inside, with the brick chimney appearing above the roofline. My parents had planted lots of pine trees on the block, which were growing rapidly. By this stage, Laurie had made a friend who was rich enough to own a movie camera and generous enough to lend it. My father was no photographer, but he did manage to capture a little of what the Marine Parade looked like in 1957 in this dark, rather wobbly footage!

Another brother, Jim, was added to the Shnookals. Each Christmas holiday, our heights were recorded on the doorjamb, and as we grew, so too did our sibling rivalry and our squabbling. But there was one thing we passionately agreed upon: - we all loved Shoreham and our holidays there. For us kids, it was paradise. We lived in our bathers and thongs during summer and overalls and gumboots in winter. We hardly ever were made to have a bath. The lower half of an inside wall was painted as a blackboard, and we spent hours drawing and writing in chalk. It didn’t seem to matter if we spilt our drinks or made a mess because we had bare floorboards and vinyl-covered furniture, so very unlike our carpeted, orderly home in Caulfield. In winter, we roasted marshmallows on our open fire, and occasionally, in summer heat waves, my mother would let us eat cereal for dinner. We were on holiday from school and our usual routine, and Shoreham meant freedom and fun for all of us.

We often grabbed plastic cups and headed for a small pond at the bottom of our block, where we fiercely competed to see how many tadpoles we could each catch. (We always let them go again, although this compassion did not extend to bull-ants on the occasions when nests were encountered.) At other times, we would take turns sitting on a metal tray and slide down steep slopes covered in pine needles, always under the supervision of our mother, and miraculously, no one ever got seriously hurt. Occasionally, we saw a movie in the Shoreham Hall or in the hall at the YMCA Camp. Later, we sat on rugs at the Balnarring Pictures. The whole crowd used to shriek with delight when possums ran across the screen, and groaned with dismay if the film broke.

In the early days, we had fresh milk from the local dairy, delivered each morning into a special pail that we left on our front gatepost, and at night, all of us kids piled into bunks in the only bedroom. Sometimes, if I was lucky, I would score my father’s empty bed in the main room and watch the lights blinking from Phillip Island before I fell asleep. Best of all, there was Shoreham Beach.

We played in the shallows of the creek when toddlers came to play in its deeper waters just before the bend. I was never a confident swimmer, so it seemed a long way across the creek. I always felt relieved when my hands hit the wooden posts on the other side, and I could stand up on the submerged concrete platform. Sometimes, we had to avoid being dunked by the kids whose parents ran the Shoreham sawmill, but generally, the resident local kids accepted us. At lunchtime, we were ordered out of the water and onto a picnic blanket in the shade for sandwiches, biscuits, and cordial. Our dog Pepper and later Rimsky were willing participants in the picnics, and I was grateful for the quick disposal of crusts.

On the way home from a day at the beach, we normally made a stop at the Shoreham General Store. In 1960, my father borrowed his friend’s movie camera again and managed to capture some priceless footage. It must have been a very special occasion because instead of having our usual icy poles, we were eating ice creams!

In the above clip, Linda Wyse appears with us, but is only one of the many kids who used to stay. Right from the start, Laurie and Ruth encouraged their friends to visit with their children. Our bunk room, therefore, was often filled with Blair and McLaughlin kids and, of course, our Valentine and Manthorpe cousins. Sometimes, even one of the Wales family would sleep over if they didn’t want to return to their house in Merricks Beach. I’m not sure how we all fitted in, but I seem to remember that sometimes there were mattresses on the floor. However, I have no idea where the adults slept, but after a few wines, perhaps it didn’t matter.

Eventually, we began to spread out. A bungalow was built, which meant that my parents were able to move out of the main living area and into their very own bedroom. A caravan also appeared on the block, mainly commandeered by my sister Shan, and then, a little later on, another bungalow was added. At some stage, our house was connected to the main water, and we could do away with our constantly leaking water tank. We zoomed around Shoreham on bikes, and sometimes, my sister Deb and I borrowed a pony called Silver from the McKillops. My older sister Shan was a fantastic riding instructor. While I never managed to learn how to stop Silver from bolting along the beach, I did, however, master the art of clinging on so tightly that I didn’t fall off. Meanwhile, Laurie bought the block of land next door, ecstatic to be rid of our noisy neighbours who periodically camped there. However, surely THE biggest change within that decade was that the Shnookals got a flush toilet right outside the bathroom! This became known as the ‘chandelier room’, named after its ornate (although plastic) light fitting.

More holiday houses were built at Shoreham, and our numbers began to swell. The Love family, in particular, was a huge addition. Unlike our mother, Jenny Love could swim. So finally, we were allowed to play in the sea, watched over by Jenny, while our mother looked after the little ones in the shallows of the creek. We all got along, generally, and even our dogs didn’t have many fights. The Loves had a beach umbrella, which I seem to remember was primarily for the benefit of their dog Dan, an elderly Dachshund, although we were welcome to use its shade, too. More importantly, the Loves also had an extensive stockpile of comic books, which they likewise generously shared with us.

Jenny and Ruth wrangled the combined Shnookal/Love tribe of nine kids together, necessitated by the absence of their husbands. Laurie and Dick were both doctors at very busy private medical practices in St Kilda and made it to Shoreham whenever they could get away, which wasn’t very often at that point in time. My father missed us a lot and Shoreham. Most evenings, Ruth drove to the public phone box outside the Post Office, put numerous coins into the slot and exchanged the news of the day with her husband until the money ran out, and they were disconnected.

Eventually, the phone box was moved to a new location outside the Hall. As time passed, so too did the demand for its service, especially during summer. A second phone box was added. My mother began to return from her nightly trips, grumbling that she had to queue up to make a phone call. It was a similar story at the General Store. En route to the beach, we would have to wait in the car for even longer than usual for our sociable mother to reappear from the shop with her newspaper. More and more beach umbrellas sprang up on the sand, making it increasingly difficult to spot those we knew amongst the crowd. Suddenly, we had to pay for a season ticket to access the beach by car, and a little man called Mr Jago appeared at the end of Beach Rd to collect a fee from those who didn’t have one.

By then, those of us with holiday houses must have far outnumbered Shoreham’s permanent residents. On a hot day, the beach was packed and, as the footage demonstrates in the link below, totally chaotic. In this clip, there are glimpses of my brothers, Toby and Jim; sister Deb on her horse Boris; Ruth; Laurie in his (misnamed) boat ‘Fingertip Control’; Bernard Rechter alongside Dick Love and his sailboat ‘The Black Pig’; an unknown speeding dog; various and occasionally bobbing Manthorpe cousins; and of course the star of the film, Shoreham beach circa 1968, complete with boathouses.

As a young teenager, I welcomed Shoreham’s burgeoning popularity. ‘Shoreham?’ my school classmates had always sniggered. ‘Where the hell is Shoreham?’ Finally, the place was on the map, even if it was mainly due to its proximity to Pt Leo. And, of course, more families in the area meant one important thing: - the likelihood of meeting new teenage boys. My two older sisters stepped up to the task by establishing connections with the Normans and the Busbys, and there were other families with multiple teenage boys, too. Summer days spent on my towel at Shoreham Beach suddenly became a whole lot more interesting!

Certainly, they were different times. Sunscreen was unheard of, whereas we all knew the value of coconut oil in achieving that perfect tan. And a hat? Not a chance! By then, I had my own horse and, therefore, rode a lot; however, I didn’t bother about wearing a crash hat. I don’t think that there was even such a thing as a bike helmet in those days. At some point, all of us teenagers stopped wearing thongs during summer holidays. We worked hard to have calloused and toughened feet so that we could walk barefoot on any surface, although I confess that sometimes I found it hard not to grimace, especially on gravel. Mind you, it was considered okay to yell and swear when you stubbed your toe on the nightly walks down to the beach in the pitch black.

From the late 1960s onwards, there were many artists and their families from Montsalvat and Dunmoochin who stayed in Shoreham. I clearly remember being confused by the appearance on the beach of a naked child with long chestnut hair who answered to the name of Di and yet had a penis. The postmistress was likewise confused when Mrs Pugh turned up at the Post Office and requested her mail a couple of hours after another, different Mrs Pugh had been in. Wide-eyed, I recall overhearing a shocked Myra Skipper telling my mother about the impending wedding of one of her sons, the first in the family for generations.

And there was my father’s story, which he loved to tell, about the time that he had trouble deciding whether to wear a tie or not to Leon and Ruth Saper’s dinner party, only to discover all the guests were completely naked. I never did learn if my father had worn a tie. At any rate, Laurie decided that he needed an artistic endeavour in order to ‘keep up with the Joneses’, as he put it, and created a lead light door with six panels.

After Laurie left his medical practice, he was able to spend a lot more time at Shoreham, doing what he especially loved: - fishing and socialising. Laurie had always enjoyed a party, and because lots of people loved ‘Snookie’, there was never a shortage of friends ready to participate. BBQs at the Shnookals became large events, fuelled by plenty of cask wine and bottles of soft drink, sausages in white bread with tomato sauce and music from a reel-to-reel tape recorder. There was usually a bowl of salad, with its obligatory iceberg lettuce, tomatoes and cucumber, placed in the middle of the table and surrounded by numerous massive containers of chips. Almost every New Year’s Eve, there was a party at the Shnookals, and everyone was welcome – invited or not. Kids, teenagers and dogs were part of the mix, as were our horses – up until the time that a fence was erected between the house and the paddock, and they could no longer join in the festivities. Parties for us teenagers generally ended with a walk down to the beach to watch the sunrise.

Ruth, too, was very gregarious. However, I suspect that she enjoyed the gatherings a lot more after the dishwasher was installed in 1977. By then, the Valentines were well-established in their own house in Marine Parade and had been attending parties for years. A new family, the Silberbergs, arrived next door. The youngest members of the Shnookals and the Loves joined forces with the Valentines and Silberbergs to become the ‘Jelly Bean Jet Set’. Unfortunately, by the time the t-shirts had been printed, the Jelly Bean Jet setters had already outgrown them.

Meanwhile, there was an astonishing development on the main street of Shoreham, between the shop and the post office. A hamburger joint, complete with a jukebox, had opened up, with a petrol station attached. Toby worked there for three consecutive summers. However, the business didn’t last long after the main road was re-routed to bypass Shoreham. By this stage, most of us kids had left home, although we all still continued to go to Shoreham. Our second Visitor's Book records visits from David Deutschmann and John Jenkins, Deb and Shan's partners. And every December, we assembled at Shoreham to spend Christmas with the Valentines.

This photo is unusual, for there is neither a Shnookal nor a Valentine dog to be seen (although I do note the presence of our cat, Dimboola). For Shnookal, dogs – first Pepper, then Rimsky and later Bosun - featured heavily in our photo albums and movies. These dogs were considered to be part of the family, not just by me, but by all of us. It was similar for the Valentines, and for the Loves. Ruth, Eleanor and Jenny would no more have considered leaving a kid behind when we went to the beach, than leaving a dog. Here is Rimsky having a great time on Shoreham Beach with us in earlier days.

Laurie Shnookal had not been well for a long time and passed away in 1982, not reaching his 64th birthday. This is how I like to remember my father, enjoying his life and his beloved Shoreham.

The following year, I quit my teaching job and lived at Shoreham to write my first novel. Suddenly, I saw Shoreham from a completely different angle. For outside school holidays, weekdays in Shoreham were blissfully quiet. At night, I listened to the waves crashing on Honeysuckle Beach, and in the morning, I awoke to the sound of birds. On my daily walk with my dog, it was rare to come across another person. Marine Parade was like a ghost town, its holiday houses all standing empty. My days were spent writing, focussed and undisturbed... Until the roar of traffic along Marine Parade on a Friday night alerted me to the fact that another weekend had begun. Lawnmowers and chainsaws would start up early on Saturday morning, and the place was a hive of activity and noise, which continued throughout that day and the next. Late Sunday afternoon, there was a mass exodus, and afterwards, peace would once more descend. I would breathe a sigh of relief and wonder if this was how permanent residents had always felt after the invading horde of us holidaymakers had departed. Without a doubt, I was glad to have my Shoreham back as I wandered up to the shop in the serenity of a Monday morning.

Of course, everyone knows that a writer generally doesn’t make a living wage. I was no exception, and so I moved away to get a job. I continued to return to Shoreham, often for parties. Just as the Shnookal house was perfect for us when we were kids, we discovered that it was also the ideal place for our parties. The bulky lounge suite was on casters, so it could be quickly rolled to one side, and with the removal of the rug, a sizeable dance area could be created with minimal effort. There was plenty of accommodation in the house and ample room on the block to pitch a tent or to park a van, station wagon or panel van. I celebrated my 30th birthday there, and several siblings likewise celebrated significant birthdays. Usually, however, we didn’t need a reason for a party at Shoreham. My all-time favourite was the pyjama party, held sometime in the depths of one winter. We kept warm in front of a roaring fire inside and a massive bonfire outside and didn’t have to remove our party clothes when we fell into bed at the end of the night. Another I specifically recall is the summer beach party that my cousin Jo Valentine and I tried to organise, only to be flooded out during one of the wettest weekends on record. At any rate, parties at Shoreham were never, ever dull occasions.

My mother didn’t attend these parties. Instead, Ruth organised her own weekends at Shoreham with her friends, frequently other activist women from the Women’s Electoral Lobby. I’m sure there was drinking at Ruth’s gatherings, too, but I doubt that there was dancing.

In March 1991, a whole new era began with the arrival of the first of a new generation of Shnookals. Toby and his wife Gina introduced their son and, then a couple of years later, their daughter to the joys of Shoreham. The heights of Matt and Jo were added annually to the marks that had been recorded for those of my siblings and me. Once again, the house rang out with the sound of small children. The kids played at the beach and, in the early days, were zoomed around Shoreham on the back of their parents’ bikes until they graduated to their own.

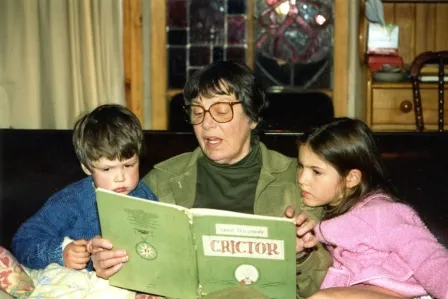

Toby and Gina continued on the Shnookal tradition of open house at Shoreham. Many of their friends brought their kids down for holidays and weekends. Paul Wright’s family was a frequent visitor, as was the family of Gina’s sister Andrea, the Staffords and others. Fortunately, the bunks had been kept, and by this stage, the bungalows had been joined together, and another bedroom added, so everyone managed to be accommodated. Ruth, an extremely doting grandmother, naturally retained her own bedroom, which she occupied most holidays, and there was always a bed for Marjorie, the children’s other grandmother. Ruth loved sharing her passion for books, and reading to the kids was one of her greatest pleasures. Here she is, reading to Matt and his cousin Daisy.

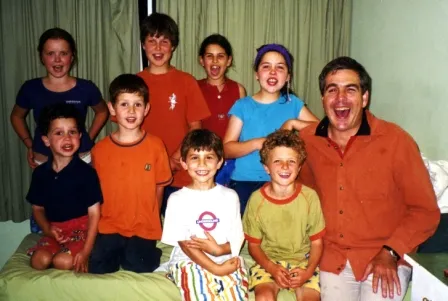

But Matt and Jo didn’t just play with the kids who were staying with them. Others in Marine Parade likewise had children, and they, too, congregated at the Shnookal house. Certainly, there was always plenty to do there, both inside and out of doors, for Toby loved organising and keeping the kids entertained. He frequently took a crush of kids on body surfing expeditions to Pt Leo. So a third generation of Shnookals grew up, revelling in school holidays at Shoreham, as part of a big mob of kids. Below is a photo of Matt and Jo with friends from new generations of Loves, Silberbergs and Wrights, plus, of course, their father, Toby, who looks as if he is having the most fun of them all!

I generally went to Shoreham outside of school holiday times. By then, I’d built a house on eight acres in St Andrews, had a stressful job in equal opportunity and was doing post-graduate studies. In addition to this, I was a volunteer trainee fire-fighter with St Andrews CFA and was involved in setting up a new local Landcare group. Occasionally, I had to give a talk at a high school about my novel ‘An Uncommon Friend. ' So all in all, it wasn’t easy for me to get away! Yet whenever I could, I headed to Shoreham to relax and recuperate. I read a lot, went for long walks and simply enjoyed the luxury of some time out. Shoreham, for me, was like the reset button on a computer, helping to reboot my way past some crashes.

Meanwhile, the pine trees had turned into a problem, and Ruth made the very difficult (and expensive) decision to remove some of them. She and Laurie had painstakingly planted and nurtured them in the early years, but even Ruth couldn’t ignore that one of her precious pine trees was nudging a bungalow wall, and disaster was sure to follow if it was allowed to continue to grow. A crane was brought in, and the process of removal of these trees provided much entertainment for everyone. Over the next couple of decades, all the pine trees were removed from the block.

Fortunately, our horses had left Shoreham by the time horses were banned from the beach and barred from the ‘backtrack’ (which runs between Prout Webb and Cliff Roads). We were also lucky that the dog restrictions came in after Bosun had died and that the other regular Shoreham dog, Tom, didn’t enjoy going to the beach. However, these days, the current restrictions on dogs make it extremely problematic, with our current six Shnookal dogs all loving to swim - a near-impossible activity whilst remaining on a lead!

In 2009, a brand-new member of the third generation of Shnookals was introduced to Shoreham by my brother Jim and his partner Vanessa. From then on, Nikolai’s height was regularly measured and recorded on the wall next to his cousins. However, little Nik barely got to know his grandmother and hadn’t even celebrated his second birthday when we lost Ruth. She was 88. Shoreham seemed very strange without her and without Tony Valentine, who had died months earlier. Around this time, too, the whole Shoreham community suffered a massive loss of its own when the General Store closed its doors.

Nevertheless, various Shnookal family traditions continued to be upheld, such as the customary practice of holding parties at Shoreham. Jo celebrated her 21st birthday there and also organised a second combined Shnookal/Valentine party with Jas and Miv. Toby and Gina’s New Year’s Eve BBQs have now become legendary. First, Merlin and then Emilie appeared at these parties, and both joined the Shnookal tribe as Jo and Matt's partners. My father’s lead light door continues to catch the morning sun and reflect our family origins in its new place of honour inside Deb’s holiday house in Hepburn Springs. Meanwhile, Shan has created a wonderful replacement stained-glass door for the Shoreham house. In addition, dear friends from long ago remain good friends today, with Paul Wright, Natasha Silberberg, and Peter Busby (plus families) all buying their own special pieces of Shoreham.

The years roll on at an increasingly alarming rate. But sometimes, there are precious moments that are captured and treasured. This is one such moment, spent with my aunt Eleanor Valentine.

Ruth and Laurie Shnookal now share a spot in Flinders Cemetery, marked by plaques on the same rock. It’s not Shoreham, but it’s close. When I visit, I place two pine cones side by side in their memory. Things continue to change. Toby and Gina now own the Shnookal house, have installed solar panels on the roof, and connected the place up to the main sewerage. However, the house relies once more on rainwater tanks, although now poly rather than the galvanised iron type of the previous era. These days, there are TWO indoor toilets, which have been the subject of much commentary on Toby’s Facebook page. Shoreham has a large permanent resident population, and its numerous community groups are thriving. The pine trees above the beach are getting taller, although with fewer branches. And the shadow that I now cast on the sand is fatter around the middle and is no longer recognisable as my own.

But just as the tide continually alters the beach, Shoreham remains intrinsically the same. It’s a very special place, and I still need to go there often. Sometimes, I sneak down, just for an afternoon, to breathe in the Shoreham air and walk along the beach. I can’t explain why I love Shoreham so much, but I do know that this will never change.

© Liezl Shnookal 2019